Farmers across the U.S. push forward to plant, and there’s an immense amount of pressure riding on this year’s crop production picture. With a margin squeeze setting in across farms, economists think it could accelerate consolidation in the row-crop industry.

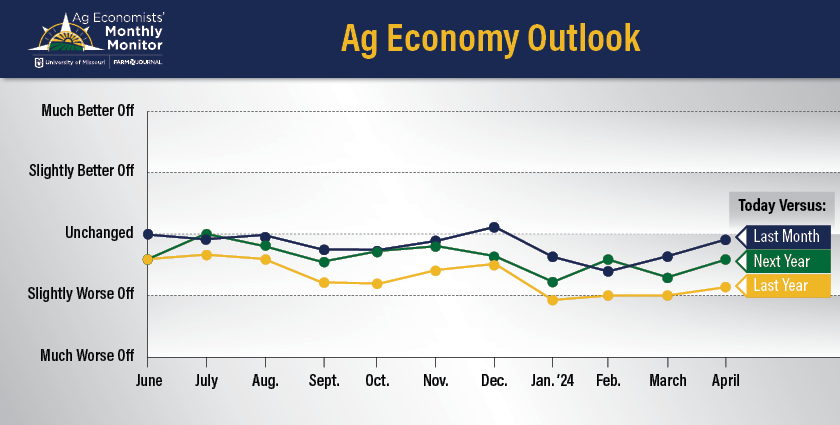

The April Ag Economists’ Monthly Monitor, a joint survey of 70 ag economists conducted by the University of Missouri and Farm Journal, shows economists views on the ag economy didn’t deteriorate from March to April. Their view on the current ag economy, when compared to 12 months ago, continues to show growing concerns.

“Everybody’s just continuing to wait and watch input prices stay high, costs stay high for producers, and for crops in particular, crop prices tending to move lower,” says Scott Brown, interim director, Rural and Farm Finance Policy Analysis Center (RaFF), University of Missouri. “Everybody’s waiting to see what weather is like this summer and what kind of crop we put in the bin.”

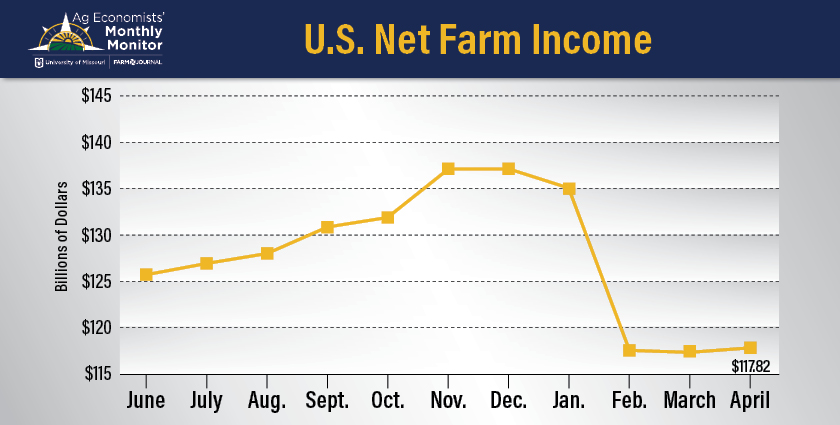

Brown helps author the Ag Economists’ Monthly Monitor. This month’s monitor shows economists expect net farm income to fall to $117.82 billion this year, which is steady with both the March and February survey results. It’s also in line with USDA’s current 2024 net farm income projection of $116 billion. However, when you consider net farm income reached $155 billion in 2023, both USDA and economists are saying they expect net farm income to drop close to 25% this year.

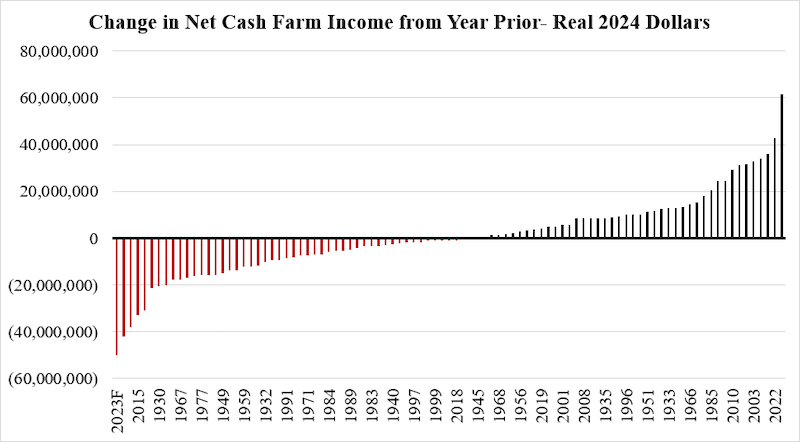

According to data analyzed by the University of Missouri, the change in Net Cash Farm Income is a strong metric to use when looking at the eroding ag economic picture. The change expressed in real 2024 dollars. It shows the 2023/24 change of $42,220,837,000 is second only to the 2022/23 change of $50,206,673,000 and means the largest and second-largest drops in Net Cash Farm Income have happened the past two years.

“I think the biggest one of the biggest concerns by far is this margin squeeze,” says Michael Langemeier, associate director, Center For Commercial Agriculture and Professor, Purdue University. “When you really start looking at ’24 budgets, I think the word I would use is ‘ugly.’ It looks as bad as 2019, maybe even slightly worse.”

Langemeier is not only one of 70 ag economists surveyed for the Monthly Monitor, he also helps author Purdue University’s Ag Economy Barometer each month, a survey of nearly 400 producers across the U.S.

“Looking through February, the Ag Economy Barometer has been relatively flat for about the last six months,” he says. “And that’s a little bit intriguing, because the prices did tumble a bit a couple months ago, and so that that hasn’t been reflected yet in the sentiment. But when you look at the biggest concerns, they’re still focusing on high input costs and low crop prices and high interest rates.”

Concerns About Consolidation in Ag

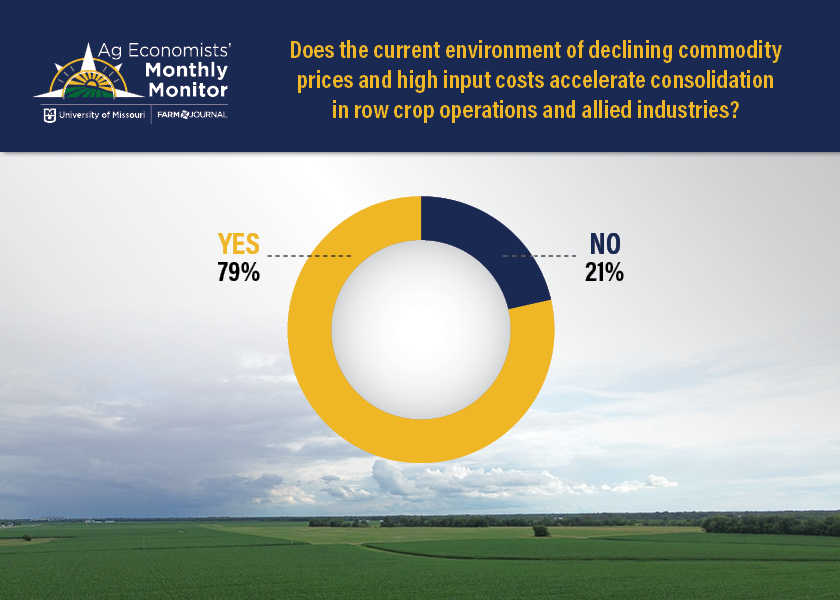

The April Ag Economists’ Monthly Monitor also asked a question about the risk of consolidation in the row crop side of ag. Economists were asked if the current environment of declining commodity prices and high input costs could accelerate consolidation in row-crop operations and allied industries. Nearly 80% of economists who responded answered yes.

“Maybe as strong of a responses as it was, it did surprise me,” Brown says. “In general, when you think about it, we’re headed to what’s likely a period of tighter margins. I think the economists were saying this is going to make this competition to get bigger to try to offset some of the tighter margins work in their operations.”

Economists said geographies at the greatest risk of consolidation are areas that rely heavily on wheat and cotton production or where drought continues to be an issue, including the Great Plains and the southeast Cotton Belt. Economists also point out areas of the Corn Belt that have marginal soils and production could also see consolidation. Economists also pointed out the size of an operation will be a factor.

“The response was smaller operations are going to struggle, those maybe more highly leveraged are going to struggle, the smaller operations might be what becomes more problematic as we look ahead,” Brown says. “Operations are going to look to grow to try to offset what are going to be tighter margins that seem to be kind of the overwhelming response that we saw from the economists.”

Economists in the Monthly Monitor also say anywhere that has high cash rents and land ownership is scarce could be at risk of consolidation. However, Langemeier says another driving factor could be the adoption of ag tech.

“One of the questions we asked on the Ag Economy Barometer for the upcoming survey, is: Do you primarily buy used or new machinery? And there’s a bunch of people who say they buy used machinery. So, guess what, they’re behind the technology curve and to the extent that this precision agriculture technology, artificial intelligence and digital agriculture, all these things that are potentially profitable, there’s going to be a segment that’s left behind.”

What other factors could cause consolidation. Economists listed a plethora of other reasons in the April Monthly Monitor, including risks for some crop suppliers.

“We are in an era of accelerated consolidation in the Corn Belt due to new technology and increasing divergence in managerial ability,” one economist responded.

“This is a trend across much of the crop sector, and the current economic environment is one of many factors at play. It may be a difference between people being happy with their choice to leave the sector, because they can sell their farms and machinery, etc., for a good price, and those who are under pressure to leave because they cannot make ends meet,” said one economist in the anonymous survey.

“Input suppliers may be at the biggest risk for consolidation,” another economist said.

“Regardless of crops/geographies, I’d say the greatest risk of consolidation is more likely among farms that have one or more of the following: 1) Farmers near retirement age without a clear successor. 2) Farmers that are highly leveraged or in weak financial positions. 3) Farmers that have less land ownership

Changing Landscape in Ag

The April Monthly Monitor also asked how falling net farm income could change the landscape of agriculture. FAPRI-MU’s latest baseline projection shows average net farm income could fall to $114 billion for 2024 to 2033, down from $145 billion over 2020 to 2023. If that forecast holds true, economists say it will impact agriculture in a number of ways, including further consolidation of operations, downward pressure on land values and cash rents, as well as reduced purchases of farm machinery and crop inputs.

“We will see a slowing of entrants in to the farming sector and a few more exits to the industry,” one economist said.

“There have been a lot of investments in machinery, farmland, etc. In response to strong farm income since 2021. That activity is slowing and may slow further if farm income stagnates at the projected levels. This is likely to slow or even reverse increases in land values,” said another economist in the anonymous survey.

“That would be a major drop and would take adjustment that may lead to some farmers leaving the industry or making other operational/management changes to adjust to the lower income environment. However, 2020 to 2023 is more of an anomaly relative to the longer-term trend of farm income. I do think farmers are aware that incomes at those levels weren’t going to last and were also preparing ahead for a downward adjustment that is expected,” was another response.

One economist pointed out while the drop in farm income will be a difficult adjustment, 2020 to 2023 was more of an anomaly, and the drop in net farm income could provide more motivation to strengthen the farm safety net.

Fight Over Finishing the Farm Bill Could Continue Into 2026

The timeline for the passing the next farm bill continues to be a mystery. The House and Senate Ag Committees continue to work on drafts, with the republicans on the House Ag committee announcing this week they expect markup to happen by Memorial Day.

House Ag Committee republicans stating the bill will strengthen the farm safety net, national security and conservation spending without cutting SNAP benefits.

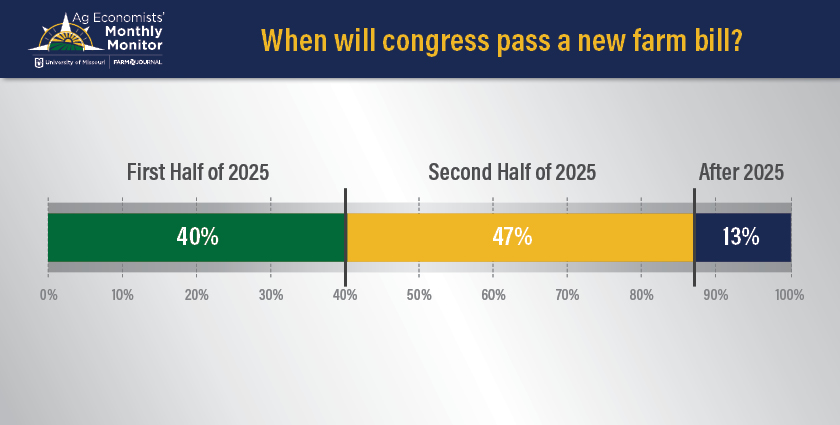

The April Monthly Monitor asked economists, “When will Congress pass a new farm bill?” None of the economists said they think it’ll happen in 2024.

- 40% think it could be the first half of next year.

- 47% say the second half of 2025.

- 13% said it could be 2026.

“I think it’s just some of the issues that we see at play today in terms of getting a farm bill to the finish line,” Brown says. “If you can’t get it done in 2024, why is it different and 2025? You’ll still have the same issues of how to find more money for some of the Title I, as well as finding enough votes to get it through the House and the Senate. I think all is going to continue to be a struggle as we look ahead. Of course, if the financial side gets more difficult, maybe that increases the likelihood of finishing sooner.”

House Ag Committee Chairman GTT Thompson recently stated of the 435 members of Congress, more than half have never debated or voted on a farm bill before. He called it a unique challenge that requires a lot of education to bring people up to speed.

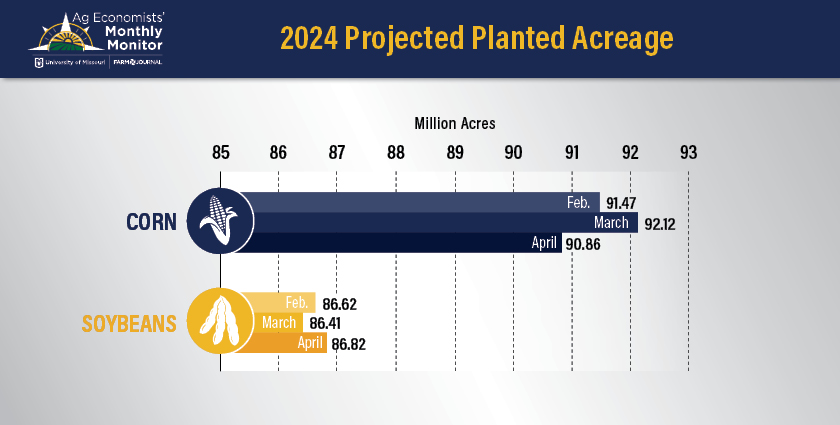

Possibility of More Corn Acres in the U.S.

Economists also weighed in on 2024 acreage estimates and in general, they think USDA largely underestimated corn acreage in the March Prospective Plantings report. If farmers end up planting 1 million to 2 million more acres of corn across the U.S., it could be an even larger weight and drive down corn prices.

Peter Meyer of Muddy Boots Ag explored the impact on prices on “U.S. Farm Report.”

View more results from the Ag Economists’ Monthly Monitor here.